Using containers for your software infrastructure have been nabbing headlines for a few years now and the enterprise is still struggling with adoption. Data governance concerns, expensive DevOps costs and a certain weariness that comes from the Silicon Valley hype machine prevents many organizations from adopting them.

So, it’s not surprising that when unikernels are mentioned the confusion gets worse. What exactly is a container and how does it compare to a unikernel? Are they the same? Are they interchangeable?

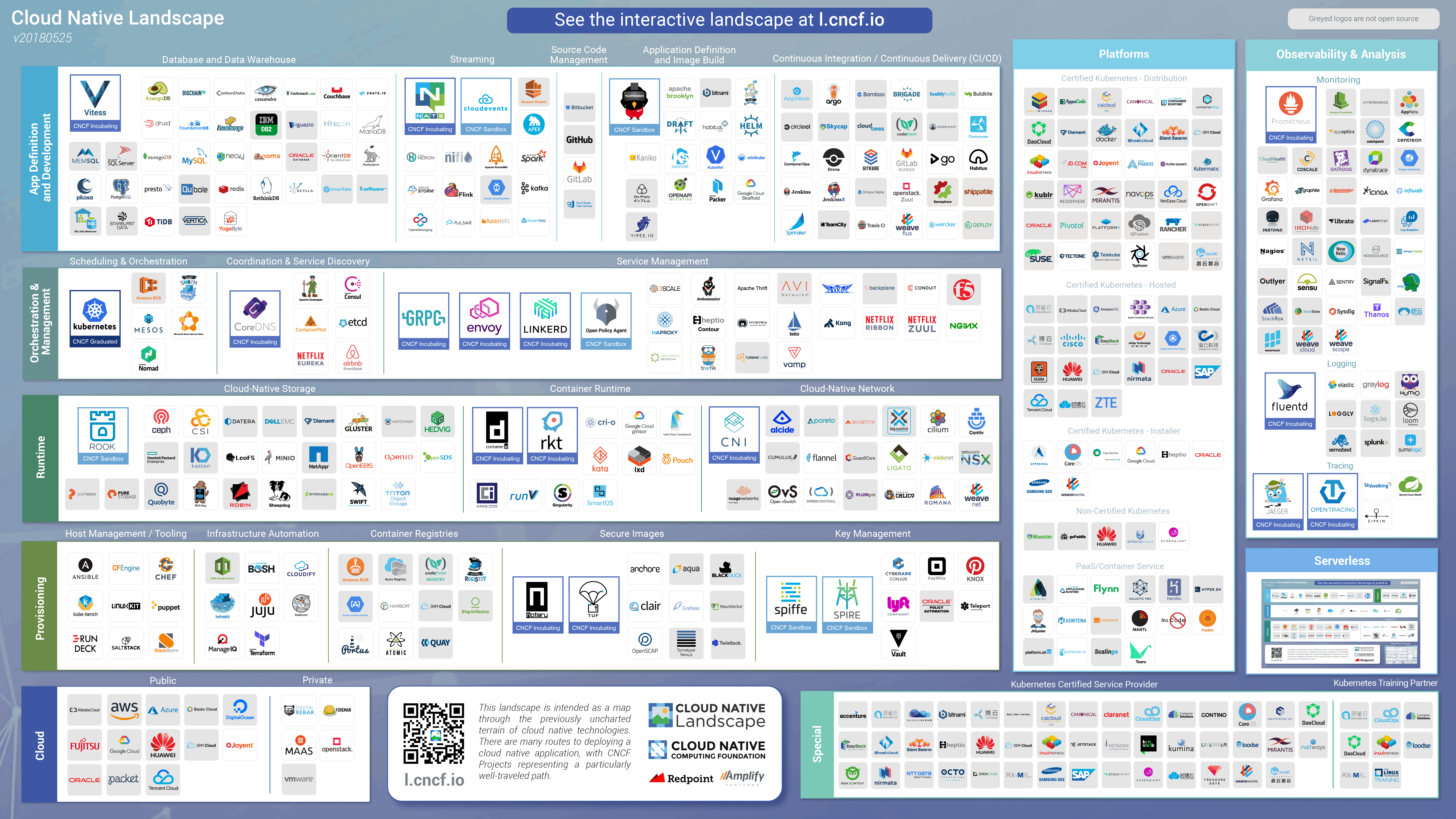

At the end of the day a container is a software deployment practice that is popular amongst DevOps practitioners – not necessarily a given software application per-se – check out the Cloud Native landscape:

Think containers are secure? Think again

The term is very confusing because it implies that the software is ‘contained’ or secure in some manner. This couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, because of the name it gives a false sense of security leading those using them to make poor security decisions. What’s more many in the industry claim that containers are a form of virtualization. Once again this is blatantly untrue. This is easy to point out as containers require Linux – the ones you see running on windows are actually running inside a Linux VM (virtual machine). True virtualization abstracts the machine. Containers can’t even abstract the operating system properly.

VMs have hardware backed isolation – code at the chip level that enforces different VMs from being able to talk to each other. Containers all run under the same operating system. So, if you can manage to break out of one container, which is trivial and happens all the time, witness the famous Dirty Cow exploit, you can then attack any other container in the system. This means that container orchestrators like Kubernetes need isolation as well.

This is a step backwards in security. Not to mention that these containers are typically given full privileges by default which breaks most security frameworks out there and should be failing every single security assessment.

In fact container security is so incredibly bad that Google has recently popularized their gVisor project to deal with container’s underlying inherent security issues. Google also notes that any container run inside their company are run inside of a VM for security purposes. Yep you read that right – they don’t trust containers more than they can throw them.

Containers does not necessary give better cost performance

As for performance – containers are typically ran on top of VMs to begin with so comparing their performance with VMs automatically makes them less performant.

Modern day virtualization also allows storage and networking IO to multiplex at the hardware level allowing extremely fast performance to the extent that the performance arguments from 10 years ago don’t apply anymore.

Lastly every organization that adopts containers tend to immediately add to their monthly cloud bill by orders of magnitude and they have to go out and hire very expensive DevOps specialists to implement this new breed of so-called cloud native software. If you thought adopting containers would drive down your software infrastructure cost you might want to revisit those costs again.

What are unikernels?

Now let’s look at unikernels. Early on it was common for IT folks to think unikernels were just another version of containers. This is simply not the case. At the end of the day a unikernel is simply a VM. What makes it different from other VMs is that it contains only one application combined with the operating system components it actually needs to work minus everything it doesn’t – which turns out to be quite a lot. Tens of millions of less lines of code, thousands of libraries, many users, and more, are left out.

As for performance, some organizations are booting unikernels in 5ms – that’s just slightly slower than calling the system call fork and two orders of magnitude faster than booting a docker container. They are also faster at run-time. Network and storage intensive applications will have a noticeable boost in performance as traditional operating systems such as Linux and Windows have to constantly switch between hundreds of applications. Unikernels only have one. Containers have the appearance of this characteristic, but they are still competing with other resources from the host operating system.

Since the average size of a unikernel is relatively small (they can be 5-10mb) you can provision thousands of them per server compared to containers that can only provision hundreds or normal VMs that are usually only 5-10 per server. This characteristic allows you to massively consolidate VM sprawl you might have. Also, since there is no concept of users or the ability to log into the host applications you don’t spend as much on expensive DevOps either.

Unikernels – More speed and security at less cost

Security is where unikernels really shine however. Unikernels have no notion of users and there is no way to log into them remotely. They completely eliminate the number one attack vector on Linux systems – shell code exploits. The very concept doesn’t fit into the architecture of a unikernel. Famous attacks from recent years such as the Apache Struts vulnerability Equifax was exposed to, or the SamSam ransomware that has cost organizations millions of dollars do not affect unikernel systems at all. That style of attack is foreign to a unikernel environment.

While some people will note that unikernels run in “Ring 0” and therefore must be less secure they fail to understand the environmental implications. First, a unikernel is a VM so it already has the same protection you find in every other software infrastructure setup out there. Also, crashing the underlying hardware is not a concern either since it’s in a VM – if you crash the unikernel, who cares? More importantly though even if you manage to successfully exploit the unikernel you can’t jump into another program since it’s one program per VM. So-called “in-memory” attacks are not new at all – it’s just another term for the same style of attack that has always existed in general purpose operating systems and that you can’t defend against. Having said that – this style of attack simply does not work in unikernel land.

To sum up, comparing unikernels to containers is more like comparing apples to oranges – they aren’t even in the same ballpark. Unikernels are faster, more secure, and will save you truckloads of money compared to container-based software infrastructure.